I’ve always struggled with the term “luxury”. There’s a dripping opulence, a Gatsby-esque quality to it.

There’s a certain magic to truly desirable “luxury” items. A timeless elegance, transcendent of trends. To me — and I’d bet many others — that’s Cartier.

Listen, I’m not about to wax poetically about le maison for the rest of this piece (nor will you see any more French; head to some Richemont site for both).

When Cartier unveiled its new releases this year, I was immediately smitten by a couple: both the Tank Asymétrique and the Santos-Dumont. But one baffled me: the re-introduction of the Pasha de Cartier. Like, if Amanda Bynes wears one, where does that really leave us? It was show over, bring in the dancing lobsters as far as I was concerned. Originally introduced in 1985 and not seen in the Cartier lineup since 2012, the Pasha is a daring and divisive model.

Reminded of Emerson’s dictum that “every object rightly seen unlocks a new faculty of the soul,” I was determined not to write the Pasha off as a large watch emblematic of 1980s excess — firmly on the Gastby side of luxury — but to understand the historical and cultural importance that led Cartier to bring it back in 2020.

A brief history of the Pasha de Cartier

Gordon Gekko and his Cartier Santos from Wall Street

The Pasha de Cartier was first introduced in 1985. A big, round watch, it was a total departure from traditional Cartier, but at the same time, completely emblematic of the brand. Cartier’s sportiest effort to date had been the two-tone Santos, a symbol almost as synonymous with 1980s Wall Street excess as Gordon Gekko himself.

As George Cramer explains, there is a legend that the Pasha’s design was actually based off a 1930s Cartier watch designed for some “Pasha of Marrakesh”, but there’s no proof that such a story is legitimate. Accounts of this 1930s Pasha seem to surface only in books after the introduction of the modern Pasha in 1985 — it could very well be that a waterproof watch was delivered to some pasha, but it seems unlikely it was large, or even round.

The Pasha was designed by famed watch designer Gerald Genta, whose list of credentials is as long as your local AD’s Batman waitlist. The design brief was to make a bold, sporty watch to compete with other sports watches Genta had already designed, but still retain the elegance of a traditional Cartier timepiece.

“The [watch from the] 40s was a very early concept that looked almost nothing like what we have today.” said Vu, owner of the Instagram account @TheCartierArchives and Cartier enthusiast. “The Pasha we know today is Genta designed.”

A classic no-date Cartier Pasha

Delivered in 1985, this first generation of the Pasha de Cartier measured 38mm in diameter, featuring four large Arabic numerals and a large bezel. These early models are easily identified by the date window at 4 o’clock with a lack of cyclops. Early production was extremely limited, and the Pasha was sold exclusively in Cartier boutiques. It looks a bit like Genta pulled from those classic Panerai military dive watch designs, injecting them with a bit of classic Cartier charm.

The watch also came with a distinct chain-linked cap with Cartier’s traditional sapphire on top, which covered up the actual screw down crown that gave the case its water resistance.

“In the evolution of Genta’s design language the Pasha marks an initial departure from strict geometry into something more sumptuous … I believe this was his first use of the sensual style of curves we see come up in his later work” said Josh Rankin, founder of Stetz & Co. “You know it’s Cartier and you’re not surprised it’s Genta”, Rankin added.

It wasn’t long until Cartier started using the Pasha as a platform for various complications: GMT, chronograph, and wild perpetual calendar and “golf” complications that are particular stand outs.

An early Cartier “Golf”: the four pushers and apertures allow for you to count the strokes of your foursome | Christie’s

The perpetual calendar’s dial was a particularly attractive design, with three sub dials and a moon phase indicator at 12 o’clock.

To confuse matters for collectors, the Pasha — even the complicated versions — was manufactured with quartz, as well as automatic movements. The automatic movements were often ETA calibers or based on such calibers.

Automatic Cartier Pasha Perpetual Calendar from 1989 measuring 38mm | Christie’s

In the late 1980s, Cartier introduced a Pasha with a grid over the crystal, lending the watch a porthole-like design akin to so many of Genta’s most famous pieces. The grid is particularly striking in the early 18k gold examples, reminiscent of early trench watches but rendered completely unnecessary by the ensuing century of human development.

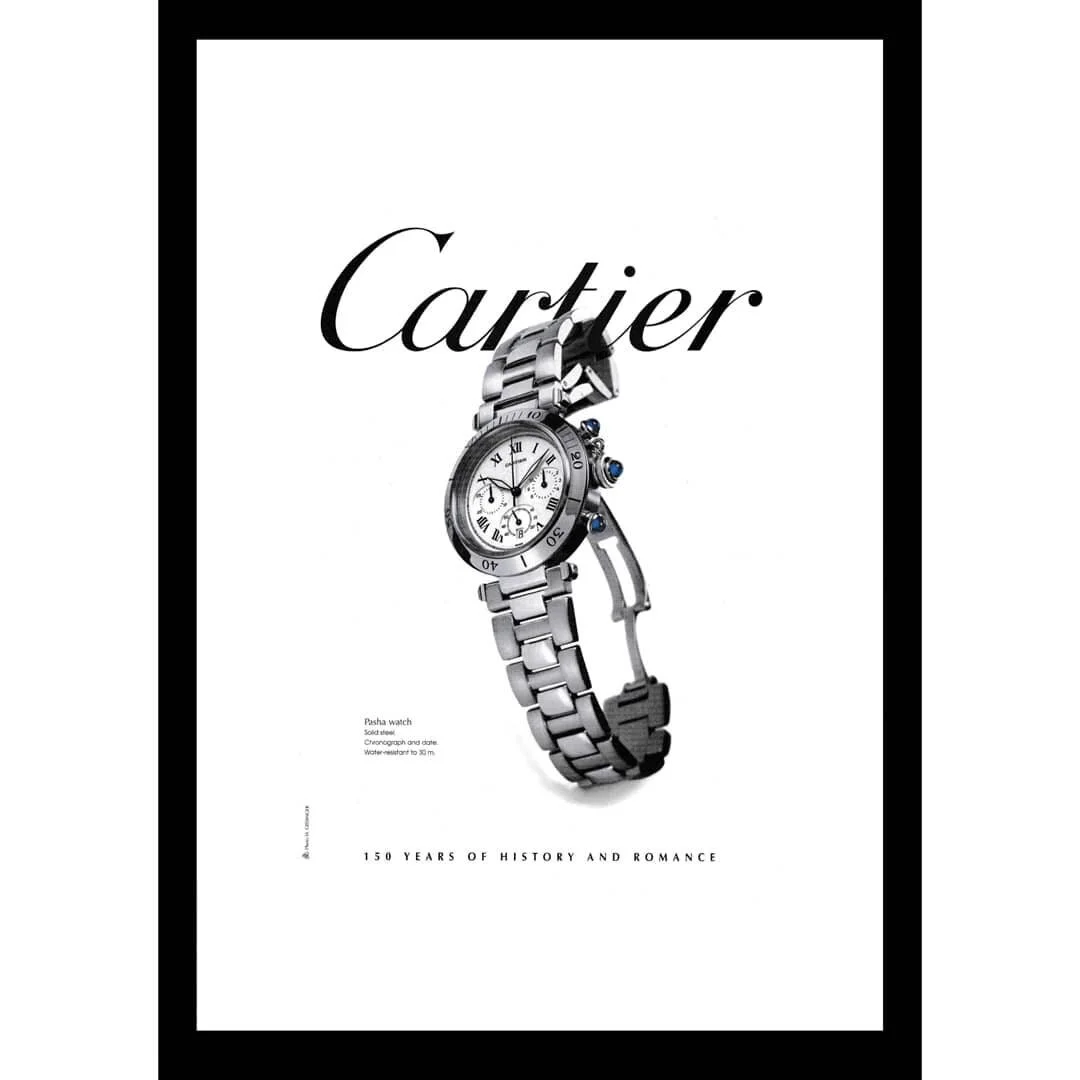

Advertising for the 2020 Cartier Pasha

While technically designed for men, women in particular took to the Pasha de Cartier as a fashion statement, something Cartier certainly seems to be drawing on in its initial advertising for the 2020 re-release. This trend among the fashionable and famous quickly rendered the Pasha its status as a modern design icon. Indeed, it’s the very reason an article such as this is warranted. Despite its status as a trendy must-have (or, perhaps because of it), the Pasha remained a divisive watch.

In 1990, Cartier released a stainless steel version of the Pasha at 38mm, making it accessible to an even wider range of customers and wannabe fashionistas.

This was followed a few years later by the release of the Pasha C, a smaller, 35mm version of the model. Cartier filled out the range with a variety of dial colors, designs, and complications to leave a little something for everyone.

In 1997, Cartier celebrated its 150th anniversary — while Cartier perhaps has an air of sophistication that other luxury brands lack, it’s not above celebrating an anniversary. It released the first Pasha in steel with a grill limited to 1847 pieces, which quickly sold out. On this success, Cartier soon released a serially-produced version of the stainless steel Pasha with a grill.

A 1990s ad for a Cartier Pasha Chronograph | @forgotten_ads

Collection Privée, Cartier Paris (CPCP) and the Pasha

In 1998, Cartier re-focused on its male customers, launching its Collection Privée, Cartier Paris (CPCP), which updated some of their historic models with legit in-house calibers. Sure, the Pasha didn’t have the lengthy history of the Santos or Tank, but it was still included in the CPCP lineup, bringing back some high-end complications.

In particular, the “Day and Night”, with a jump hour and day-night indicator was limited to just 20 pieces. A skeletonized Pasha tourbillon in white gold was also produced, this model limited to just 10 pieces. As we’ll see, Cartier thought so highly of this effort that they brought it back in 2020. To develop calibers for its CPCP collection, Cartier often worked with historic movement manufacturers like Frederique Piguet and Girard Perregaux.

Cariter Pasha “Day and Night | Phillips

Additional models were introduced in 2005 for the Pasha’s 20th anniversary, offering models in golds and then in steel. Cartier would go on to release a few more complicated models of the Pasha through 2012, before temporarily retiring it from its catalog.

The Pasha de Cartier in 2020

I’d never given much thought to the Pasha — I highlighted a Pasha Golf earlier this year because I’d never seen the complication before and I thought it was perfectly Cartier. But other than that, I pretty much wrote off the Pasha as a fashion novelty, just a notch below your typical fashion mall Fossil in my ranking of watches likely worth of my fits of snobbery and disdain.

But when Cartier re-released the watch this year, I dug a bit deeper about the watch’s history and meaning, not only to Cartier, but to the culture. Look, do I find the watch irresistibly attractive? No, absolutely not. But it’s undeniable that the Pasha meant something.

Born amidst the excess of 1980s Wall Street that was fueled mainly by masculinity and bravado, the Pasha endured, as a symbol of … well, I’m not going to mansplain what the average woman in the 1980s wearing a big, round 38mm Cartier may have been thinking, but suffice it to say: that’s badass.

And here we are in 2020: one more Wall Street movie under our belts (oh Shia, you’re so much better than that), Wall Street excess and Cartier Pasha still firmly in tact. As Rankin pointed out, it was one of Genta’s first sports models to feature sumptuous, curved lines. It’s no coincidence that the first large sports watch with a softer elegance was developed for Cartier. Further, it’s no coincidence that it’s this same model women took to as their means of expression through wristwatch. Big and bold, but with the elegance that the Nautilus or Royal Oak might lack.

”Cartier did a good job with the new Pasha de Cartier lineup. The design is surprising faithful to the original,” said Vu from @TheCartierArchives.

And it makes sense, doesn’t it? Sure, Cartier released a 35mm and 41mm version of the Pasha this time around and we’ll have a steel version off the bat instead of the first one-size-fits-all 38mm precious metal versions from 1985, but hey, times are a little different. But not that different. The 2010s were a pretty wild ride upward for the stock market, and even amid the coronavirus shock, Wall Street is doing, like not that bad?

That a watch could be as fitting for the moment in 1985 as it is in 2020 is, like I said: not luxury, but magic.

It’s magic, because we assign more than monetary value to these objects: they tell us, and others looking hard enough, something about ourselves. Someone wearing a Pasha de Cartier isn’t trying to say “look at me, I’m rich” (there are much better wrist accoutrement for that), they’re trying to communicate something just a bit deeper: perhaps about their design sensibilities, their position in society, or how they view the world.

That a singular object can communicate all that is magical.